##Two weekends ago marked the 7th annual Mozilla Festival (Mozfest) held at Ravensbourne College in North Greenwich, London.

This year I had the chance to mentor a couple dozen science + coding projects alongside the amazing Rob Davey of the Genome Analysis Centre (TGAC) in Norwich, England. Formed just three years ago, the Mozilla Science Lab (MSL) has grown to attract a broad field of science projects to the annual festival, providing a meeting place for technologists and scientists…and everyone in between.

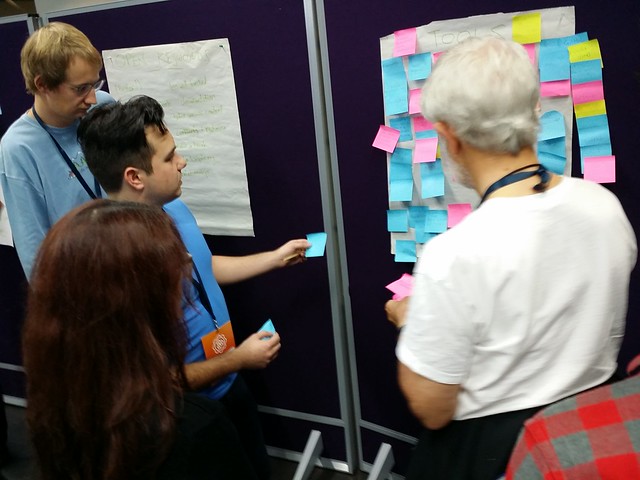

Image by Mozilla Festival on Flickr / CC BY

This year’s festival was unique in that the first round appointees of MSL’s fellowship program were on hand and ready to jump in and get involved with projects coming from around the world to hack and share their work. Also making this festival distinct from previous events was the Open Science Accelerator workshops to prepare 10 projects for sprint/hack sessions on Sunday. Rob, myself, and the fellows (Joey, Christie, Jason, + Richard) dedicated time to helping these projects transition from idea to barely viable product (BVA) over two days, consistently leveraging #openscience tools and methods to help bring things to life. In addition to 1:1 mentoring during Saturday’s session, running the science floor 9 help desk, and casual conversations in the hallways, Rob and I were invited to facilitate a “How to Run an Open Source Science Project” workshop. An early brainstorm with Karthik Ram led to the development of an informal, unconference approach to a conversation about open (mostly Web) tools and methods that can support these types of projects.

Here are mine and @froggleston's slides from the Open Source Science Project session at #mozfest /cc @MozillaScience https://t.co/LNCpee9fb8

— Billy Meinke (@billymeinke) November 7, 2015awsm info & discussion at #mozORA How to Run an Open Source Sci Proj. Thx @billymeinke @froggleston @MozillaScience! pic.twitter.com/F7hrhqPCOJ

— David Bild (@dbild) November 7, 2015Rob and I constructed slides while working at the help desk on Saturday morning, refining them throughout the day to fit the scope of the topic (which is much larger than could be covered in an hour) and the audience (which included many folks who were potential contributors to open science projects). The level of expertise in the room was excellent, which lended to well-rounded contributions to the walls of ideas we built during the session. See the slideshow below to see the general structure of the session, and note the three stopping points/prompts at which we collected ideas from everyone in the room: Closed (?) science, Open (!) science, and How to Get There.

We began by brainstorming what it means for science to be “closed.” What words come to mind when you think of a science project being locked down, hidden in some way? What does that mean for anyone who wants to build on the latest scientific discoveries? Below are keywords collected during the group discussion.

###Keywords and terms that describe “closed” science projects

- proprietary

- protected

- not reproducible

- limited dissemination

- lack of interoperability

- limited trust/opacity

- paywalled

- divisive

- positivist

- sponsored funding

- lost code/data

- docs only

Many of these terms apply broadly in both software and research communities, of course. And while we continue to support the idea that openness in science (as in many things) is a spectrum and not an on/off switch, many of these terms represent science that is done in a black box.

Next, we made a similar ask of the group; this time identifying keywords and ideas that describe science done openly. What’s unique or special when science is open?

###Keywords and terms that describe “open” science projects

- better

- free as in beer + speech

- open source

- low cost to produce

- efficient

- less duplication

- collaboration

- more vulnerable

- legality

- less well-trusted

- documentation

- better version control

- community + mentoring

- make or break

- interdisciplinary

- relationships

The terms collected in this brainstorming session largely point to the advantages and benefits to running an open science project over, say, a closed one. There were, however, terms that indicate a vulnerability aspect to science done openly, and there should be. If doing all of your science out in the open was easy, fully published on the Web for everyone to analyze and build on, everyone would be doing it. The truth is, there are real barriers to open science, and many of them reside in the social, financial, and personal career domains of science.

The real meat of the session came next, where we undertook a massive mind meld as a group of 30+, sharing which tools, methods, and ideas can help us open up science. Even if a particular tool wasn’t “open” in all aspects, it still might help an open source science project get off the ground. And what about the social and community aspects of successful projects? How do we bring new contributors of all kinds to our work? The ideas and responses ranged from very specific tools to very broad concepts, but all are worth taking a look at if you’re interested in participating in an open source science project at various levels.

###The means, how we get from closed to open

- Github/Git (x13)

- Trello (x7)

- Slack (x6)

- Bug tracking software - Bugzilla, Jira (x5)

- Stack Overflow (x4)

- Twitter (x4)

- Google Drive/Docs (x3)

- Group chat like IRC (x3)

- Mailing lists (x3)

- Web conferencing tools (x3)

- Wikis/documentation (x3)

- Jupyter notebooks (x2)

- Docker (x2)

- readthedocs.org (x2)

- EpiCollect (x2)

- figshare (x2)

- Advertising/promoting your open project

- Bitbucket

- Competitions/challenges/hackathons

- Contributorship guidelines for code + style

- Dat

- Github 101 resources

- Identified contributions needed and low-hanging fruit

- Knitr/Sweave/Babel

- Markdown

- MSL’s Working Open Guide

- Personas + user stories to help ID and bring on new contributors

- P2PU School of Open + School of Data courses

- Public recognition/rewards (badges)

- Open domain resources (data, ontologies)

- Open Notebook Science

- opensensors.io

- README file in a code repository

- Shared use cases to focus aims (ie human genome project)

- Talks about working in a distributed way

- Using real accessible data in reports

- Web-based programming languages (R, Python, Perl, etc)

- Youtube

- Zenodo

This list was the most interesting of the bunch for me since the stage had been set and the group was asked to provide the means by which science projects can transition into a condition of openness. When there was already a post-it note on the board with their tool or idea, participants placed a check mark or +1 so we could have a less cluttered count. Topping the list by a longshot was Git, specifically the use of Github code repositories for storing/collaborating on scientific software. Second from the most popular, task boards like Trello can help projects get organized and make it easy for contributors to know how they can jump in. Third most popular was Slack, the rich online chat room tool used in many organizations to support real-time conversations around projects. When you look at these top three tools, it’s not hard to pick out a few fundamental steps that can make for a more successful open source science project:

- Put your code and data somewhere people can work with it (Github, Bitbucket, etc.)

- Let everyone know what you’re working on and what needs attention (Trello, Bugzilla, Jira)

- Have a social meeting place, where people can get in touch (Slack, mailing lists, etc.)

Now, the lists above shouldn’t be taken as the only required steps to building a community of contributors around an open source science project, but they are a good start. Each tool or method or idea should be considered as an ingredient in your cupboard, or a tool in your kit, or a piece of the platform where your open science project is being built. Finding that perfect recipe takes time and is specific to the context of your projects, but many of these tools are being used right now in real open science projects on the Web. It’s up to you to explore what works for you.

##Pulling it all together

I’d like to thank everyone that participated in the “How to Run an Open Source Science Project” session at this year’s Mozfest, and I hope that everyone involved was able to take something of value from the session. Over the course of the entire weekend, there was a buzz about, an electric sense of community that was woven into each session, each code-hacking sprint, and each conversation on the 9th floor of Ravensbourne College.

And even though the festival has concluded for this year, there’s no reason to lose track of what’s happening at the MSL. Find out more about how science projects that leverage the Web are finding their legs, and how projects that already have momentum are moving into the next stages of development. Check out more at mozillascience.org, listen in on the MSL mailing list, or venture to the community forum space and see what’s going on.